Utilizing Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback in a Patient With CVA to Improve Psychophsyiological Coherence

By Amanda Call, MA, OTR/L, Draper Rehabilitation and Care Center, Draper, UT

At Draper Rehabilitation and Care Center, we treated a 74-year-old female patient who sustained L hemispheric hemorrhagic CVA. She presented with a host of symptoms, including R hemiplegia, dysphagia, aphasia, R neglect, malnutrition, HTN, pain, muscle spasms, constipation, depression, anxiety, neuropathy, GERD, nausea/vomiting, hyperlipidemia, and R foot and coccyx wound.

The patient spent approximately two months in a rehab hospital, followed by two months in another SNF, then came to AVR four months after her admission to the hospital. She was six months post-CVA at the time of this intervention and was reaching a plateau with therapies because of difficulty regulating her emotions, which caused increased tone and aphasia.

As the therapists involved with the case brainstormed ideas to address the barriers preventing the patient’s progress, the patient’s ability to self-regulate emotions and physiological states came up as a common barrier that was limiting progress and functioning. At this time, OT learned about heart rate variability biofeedback and theorized that the patient might benefit from this intervention to facilitate self-regulation skills. She suspected that teaching the patient to control heart rate and breathing would help with emotional regulation as well as improving tone and aphasia, which would allow her to progress with her therapy goals and become more independent.

Literature Review

“Heart rate variability is a measure of the naturally occurring beat-to-beat changes in heart rate.” (McCraty et al 2004). When an individual’s respirations and heart rate are at an optimal frequency, this is referred to as coherence. Coherence is “the maintenance of a physiologically efficient and highly regenerative inner state, characterized by reduced nervous system chaos and increased synchronization and harmony in system wide dynamics” and “is conducive to healing and rehabilitation, emotional stability, and optimal performance” (McCraty et al 2004).

Research studies suggest that “individuals with brain injury and impaired self-regulation often display HRV patterns with reduced HRV” and speculate that interventions which address HRV “could directly enhance the ability to self-regulate.” (Kim et al 2015).

A study of individuals with severe brain injury found that there was an association observed between HRV coherence and improved emotional control, attention, life satisfaction, self-esteem and self-awareness and concluded that “HRV biofeedback has promise as an effective, cost-efficient method for improving self-regulation in individuals with severe brain injury” (Kim et al 2015).

An additional study of individuals with chronic brain injury found that there was an association between HRV training and the regulation of emotion and cognition and that “individuals with severe, chronic brain injury can modify HRV through biofeedback” (Kim et al 2013).

Intervention

OT facilitated seven treatments utilizing heart rate variability biofeedback training during a period of three weeks. Interventions were completed using a computer-based system that tracked heart rate using a pulse oximeter and created a visual representation of heart rate variability on the computer screen. The visual representation was in the form of a line graph and a bar graph, but the system also allowed for the feedback to be given in the form of a variety of games. This patient preferred to receive feedback through the games.

This intervention was used as a preparatory activity for ADL tasks such as toileting. At the beginning of this intervention period, intervention focused on discussion of toileting because toileting was a task that caused significant fear for the patient, resulting in increased tone, difficulty communicating and difficulty problem solving to complete the task.

As the patient improved her ability to modify her heart rate variability, intervention progressed to toileting in the therapy gym, then in the patient room and with her CNAs. Furthermore, as the patient became better at regulating her physiological states while using the program, therapists began encouraging her to apply the strategies during ADL tasks. For example, if the patient became upset or frustrated during toileting, the patient was encouraged to close her eyes and picture the biofeedback games.

Example of game available in emWave Pro™ program. As patient coherence improves, the rainbow extends to the pot of gold and gold coins can be earned.

Results

During the three week period after initiating the intervention, the patient showed improvement in the following areas of OT functioning: View here: HeartMath – Draper

Using the Life History and Profile, OT was able to identify purposeful and meaningful activities the resident enjoyed, including:

Using the Life History and Profile, OT was able to identify purposeful and meaningful activities the resident enjoyed, including:

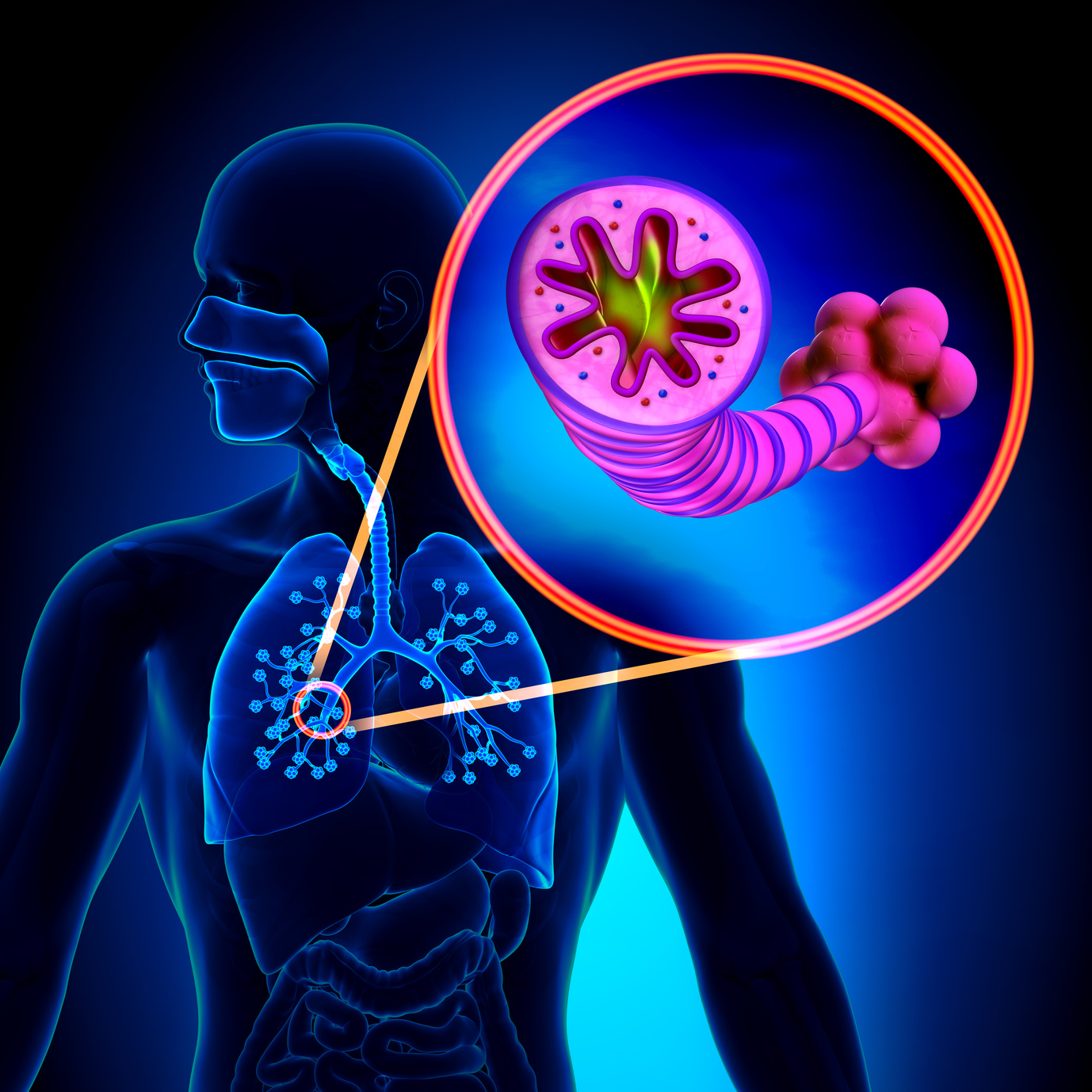

At Northeast Nursing and Rehabilitation, we cared for a 77-year-old white male who had been recently hospitalized for acute cholecystitis. His PMH included CAD, a pacemaker, cardiac stents, HTN and COPD. The patient presented with a variety of problems, including debility, decreased ADLs, poor static/dynamic and sitting/standing balance, decreased mobility, decreased aerobic endurance and breathing abilities, and poor phonation.The patient also had decreased breath control, able to produce only three words without taking a breath. He required constant oxygen and had little diaphragmatic breathing, possibly related to the secondary effects of COPD.

At Northeast Nursing and Rehabilitation, we cared for a 77-year-old white male who had been recently hospitalized for acute cholecystitis. His PMH included CAD, a pacemaker, cardiac stents, HTN and COPD. The patient presented with a variety of problems, including debility, decreased ADLs, poor static/dynamic and sitting/standing balance, decreased mobility, decreased aerobic endurance and breathing abilities, and poor phonation.The patient also had decreased breath control, able to produce only three words without taking a breath. He required constant oxygen and had little diaphragmatic breathing, possibly related to the secondary effects of COPD.

admission at Olympia Transitional Care and Rehabilitation.

admission at Olympia Transitional Care and Rehabilitation.

Consider the following patient profile: A 19-year-old with traumatic brain injury secondary to assault presented with moderate deficits in immediate and short-term memory as well as temporal and spatial orientation. He was also legally blind as a result of his injury.

Consider the following patient profile: A 19-year-old with traumatic brain injury secondary to assault presented with moderate deficits in immediate and short-term memory as well as temporal and spatial orientation. He was also legally blind as a result of his injury.